There’s a certain sentiment when it comes to storytelling I’ve heard across the internet and even from my own friends that I’m really not very fond of. It has to do with the hero’s journey. If you assume the journey encompasses all stories (it doesn’t, but let’s just assume), then there must be a finite number of stories possible, and therefore one day they’ll get run out. I’ve heard a similar question posed about music. Can we ever run out of songs to play? Are there a finite number of musical combinations to use? Similarly, will we run out of stories to tell some day? Personally I think the answer is no, and today I want to explain why I believe that is.

I love video games, and games in general, because so many of them are capable of generating unique stories, over and over again. The oldest known games all excel at this. Go, chess, backgammon, card games, racing (arguably not a game, I will admit), all of these offer a powerful emotional incentive to keep playing. Not to mentions all the procedural video games that have come about, from 4X games, to roguelikes, to loot and shoot games. Each instance of all these games plays out uniquely, creating a framework for stories to be told. Chess is the story of battle, played out in endless tactical and strategic interactions that get most complex as the game reaches a climax in the midgame. Go is the story of territorial conquer, each piece a sentinel marking off the board in the player’s favor. Stellaris is a space game where you play as an interstellar empire, ruling civilizations, engaging in warfare or diplomacy, and evolving your species to new heights. Why do these games seem to have infinite replay value? Two of those we’ve been playing for centuries, if not millennia, and I can tell you my steam account has an unhealthy number next to the stellaris playtime. How can a new story be told in each instance if these games have set frameworks and finite outcomes? In other words, why keep playing if we know there are only so many endings? I think the reason will also tell us why we can’t reasonably run out of stories.

The underlying mathematics of these games offer an incredible amount of variation. Like, mind boggling amounts of variation. Due to the mathematics of factorials, one of the fastest growing functions, when you thoroughly shuffle a deck of cards you’re more likely to have gotten an order that nobody has ever seen than one that has occurred in the past. Similarly, there are more unique variations of the game of go (about 10140) than the estimated number of atoms in the observable universe. Don’t believe me? Well here’s why:

The permutations possible in a deck of cards is equal to 52!, with the ! being the notation for a factorial. What is that exactly? Well it’s the product of all positive integers less than or equal to a given positive integer. In other words, 52! is:

52 x 51 x 50 …

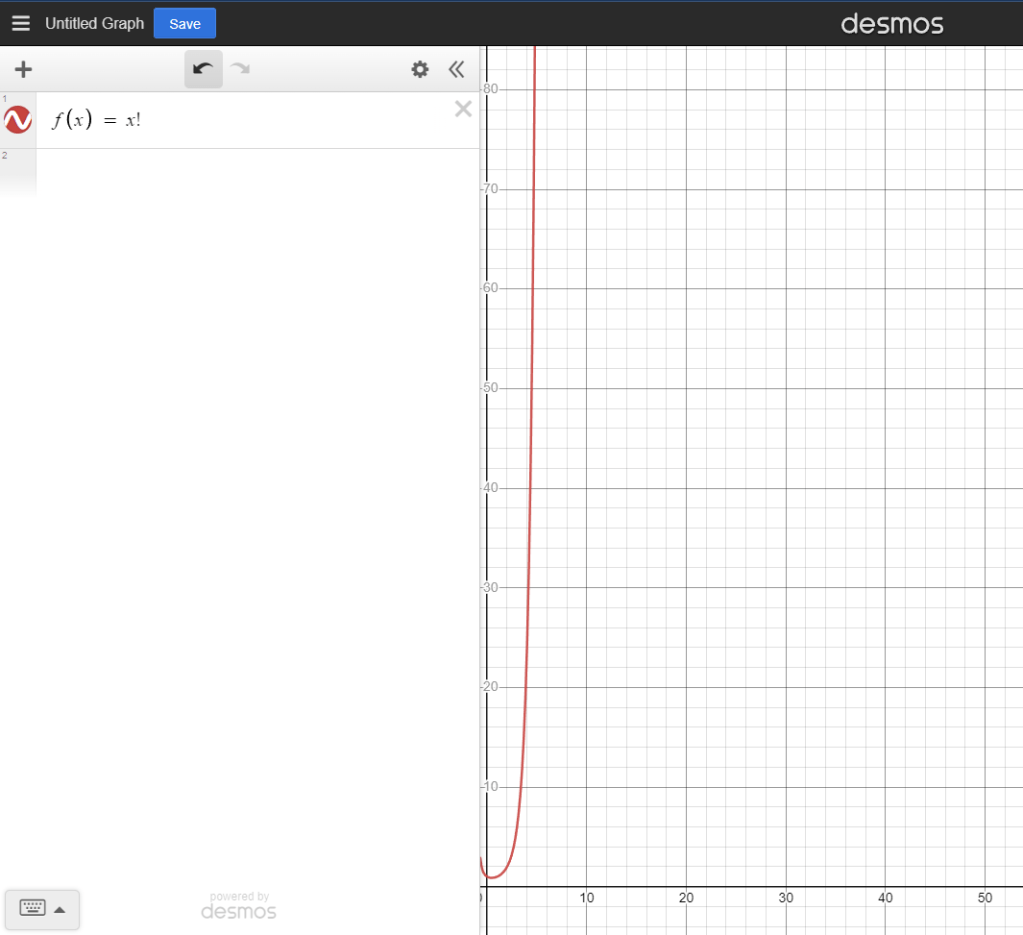

The first card could be any of the 52 cards, the next card could be any of the remaining 51 cards, the next card is drawn from the remaining 50, and so on. These numbers get big. Really big. Here’s a graph of the factorial function where f(x) = x!

As you can see, it gets big quick. We can only see out to x = 10, but the line goes way off screen, up too high to even spot. That’s because 10! equals 3,628,800. That’s pretty big, but what about 52!, the number of variations in a deck of cards? Let me zoom out a little …

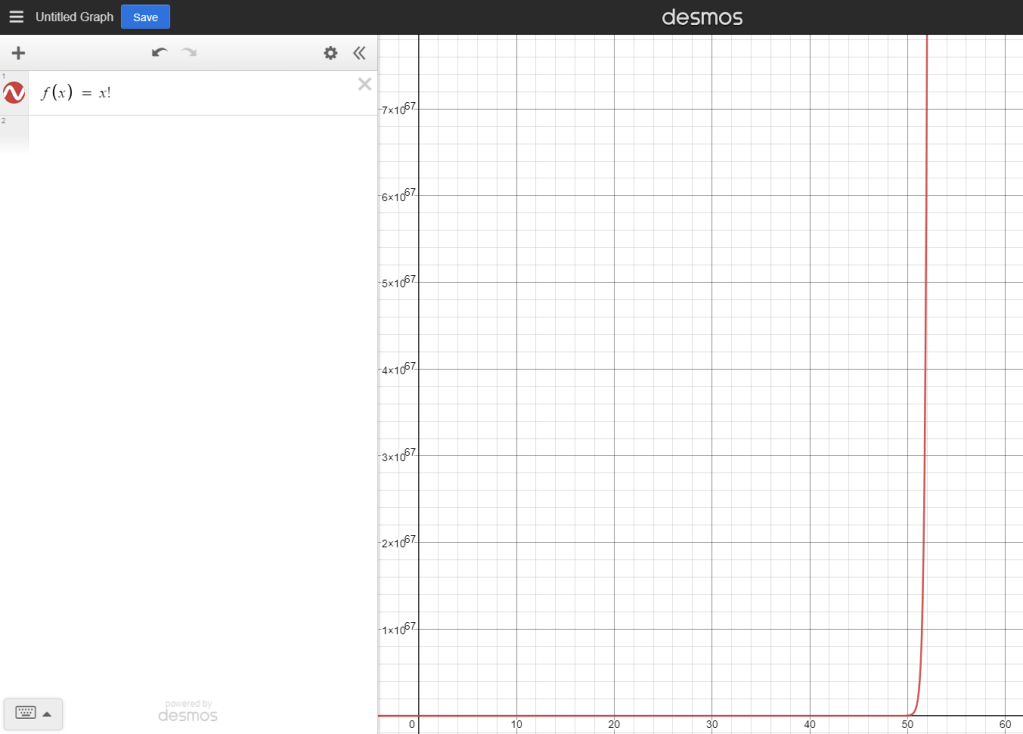

I can’t see it. Let me keep zooming out.

Ah, there we go. But hey, why does the graph look so different now? It has a horizontal line where the vertical line used to be before spiking up again at x = 52. This is because the difference between 50! and 52! is so much greater than the difference between 1! and 50! that the slope of the line absolutely dwarfs the rest of the function. It grows faster between 50! and 51! than it does all the way from 1! to 50!. Remember, we saw a growth of 1! = 1 all the way to 10! = 3,628,800 … let that sink in a minute.

According to https://www.ibisworld.com/, there are 4,792 casinos in the world. The MGM Grand in Las Vegas has 103 tables. Let’s assume that 100 tables is representative of the average number of tables per casino (the MGM grand is one of the biggest in the world, making this a pretty huge overestimate), meaning that there are 479,200 tables in the world. The most popular card games in the world are blackjack and several variations of poker. Some games use more than one deck of cards, so lets assume each table uses an average of 4 decks, shuffling one deck every hand for poker, and all the decks every round for blackjack. You can play about 75-100 hands of poker in an hour, and about 50 rounds of blackjack, so lets just say there are 75 rounds per hour x 2 shuffles per round, making 150 shuffles per hour, or 2.5 decks of cards shuffled every minute per table. Again, probably an overestimate.

That makes for 479,200 tables x 2.5 decks per minute per table, for a grand total of 1,198,000 decks of cards shuffled every minute here on planet Earth. Lets extrapolate this number to the past to the day poker was invented in the year 1829. Obviously this too will be a huge overestimate given the growth of the casino business worldwide, but blackjack was invented in 1700, so maybe it will even out.

That’s 101,966,400 minutes, which makes for 1.2215575 x 1014 or 122,155,750,000,000 decks shuffled since poker was invented. I’m not sure we even have a word for that many commas. If we do, I don’t know it. That’s an absurdly large number of decks shuffled. We must have repeats all the time, right? Wrong. Compare this to the number of variations in a deck of cards and you get:

1.2215575 x 1014 / 8.0658175 x 1067 = 1.51448691 x 10-54

Or …

.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000015144 …

It doesn’t even fit in the margins! We could have been playing cards since the dawn of the universe and still missed the number we’d need to shuffle a tenth of a percent of the total possible decks by about 35 zeros. We haven’t scratched the surface of the number of decks possible in all our cumulative years playing cards. If each hand can play out differently based on the permutation of the deck, there are so many ways poker can go that it’s no wonder we can’t stop playing it.

Yet still, people wonder if an open framework like a song or story that can hardly even be defined will ever run dry. Will a brand new form of story be told every day? Probably not. Will a lot of them feel similar? Most definitely. But will we ever run out completely? I don’t think it’s possible. And if you’re bored with all the stories told today, maybe that’s a sign you should go write your own.

Thank you for reading,

Benjamin Hawley