I’ve been listening to a lot of Erik Satie while writing lately. He was a French composer from the late 19th and early 20th century whose music you’ve likely heard even if you don’t recognize the name. Probably most famous for his Gymnopédie No. 1, he was an experimentalist, eccentric, and also a creative writer, though he’s less famous for his writing than his music. Most of his pieces were for solo piano, and he famously coined the term furniture music, music that is meant to be played in the background and largely ignored. In fact he encouraged people to ignore the music. It wasn’t just a byproduct of his composing, but the goal he set out to achieve. His music suits writing perfectly for that reason, and I wonder if he composed it with his own writing in mind. After listening to some of his music, I got more interested in the man himself and started reading.

He wrote primarily for the press, but unlike many of his musical contemporaries, he wasn’t interested in music critique. His biographer described him as “an experimental creative writer, a blagueur who provoked, mystified and amused his readers.” I couldn’t help but notice his work read a lot like the more outlandish stories from Mark Twain, especially one of his most infamous pieces where he claimed to eat dinner within four minutes, and to exclusively eat white foods, including bones and fruit mold. He said this about his American influences:

“I also owe much to Christopher Columbus, because the American spirit has occasionally tapped me on the shoulder and I have been delighted to feel its ironically glacial bite.”

I can’t help but feel he must have been thinking about Twain in some capacity when he said this.

When he did dabble in music critique, it was for music nobody else had the privilege of listening to. He wrote a piece lauding Beethoven’s Tenth Symphony, which does not exist. He also wrote about a family of instruments known as cephalophones, which do not exist either, but apparently have a 30 octave range and are “impossible to play.” I was curious about how he came up with the name, and after looking into it I’m pretty sure it must be related to his love of old church music and his study of religion in general. There’s no such thing as a cephalophone, but there are cephalophores, saints that carried their decapitated heads in their hands. I can’t see any relationship other than the name though. Maybe it’s a musical pun that goes over my head.

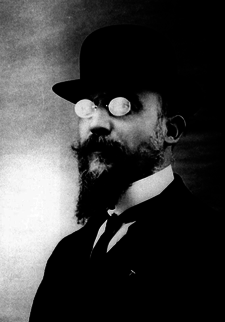

Among his other eccentricities, he went through several distinct periods of attire and personality. Here is his most well known persona.

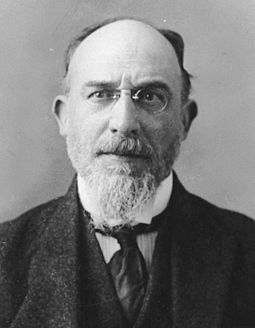

At some point before this final persona, he decided to wear nothing but identical velvet suits, having seven of them that he rotated through so that he always appeared to be wearing the same thing every day. Personally, I’m glad he moved on. Here he is in his later years. As you can see, the man took a consistent portrait.

He came to the widespread attention of the musical public in his 40s after some of his early works were played at a concert hosted by the société musicale indépendante. Many young artists were inspired by his music, and suddenly he was “the precursor and apostle of the musical revolution now taking place.” He was friends with one of the most famous composers of his time, Claude Debussy, but they had a falling out before Debussy’s death, and Satie refused to attend his funeral. Satie had several similar falling outs with various groups of students, moving from one group to the next as each in turn threatened to eclipse his fame. He had few friends that stayed with him for the long haul.

Satie died in 1925 from cirrhosis, having been a heavy drinker all his life. Picabia, a French avant-garde painter, was one of the last people that Satie worked with, and a friend of his. He made a comment on Satie that seems to sum him up as person very well.

Satie’s case is extraordinary. He’s a mischievous and cunning old artist. At least, that’s how he thinks of himself. Myself, I think the opposite! He’s a very susceptible man, arrogant, a real sad child, but one who is sometimes made optimistic by alcohol. But he’s a good friend, and I like him a lot.

Thank you for reading,

Benjamin Hawley